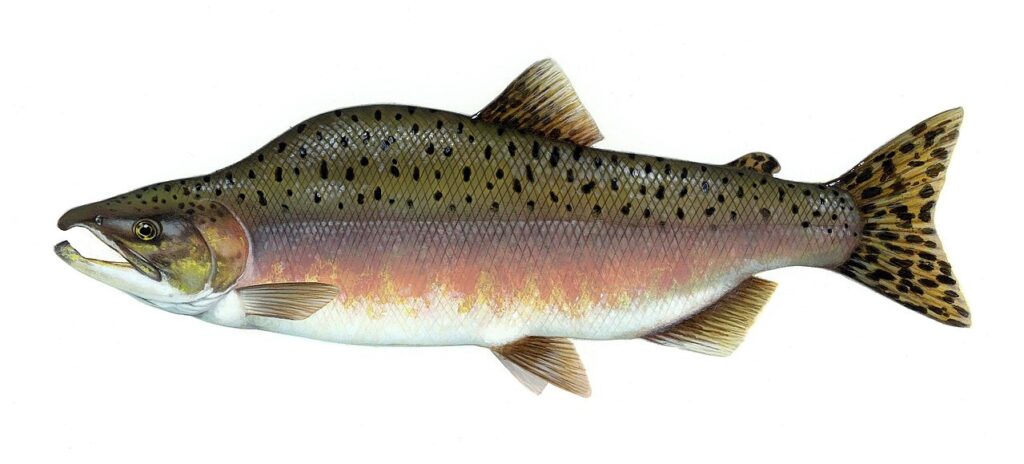

Lake Superior Pink Salmon

Pink salmon or humpback salmon, Oncorhynchus gorbuscha, are the smallest and most abundant of the Pacific salmon in their native habitat. The scientific species name is based on the Russian common name for this species gorbúša which literally means humpie.

There have been many rumors swimming around over the years as to how Pink Salmon became full-time residents of Lake Superior. Time to know the real story.

In 1955, pink salmon eggs from British Columbia were flown to Thunder Bay, Ontario, with the intention of raising them in a hatchery and stocking them far to the north in Hudson Bay. In 1956, the hatched fingerlings were loaded onto seaplanes and transported north. How and why remains murky, but approximately 21,000 were inadvertently left behind at the hatchery. Rather than simply letting them die, Ontario MNR staff released them into the nearby Current River which flows through Thunder Bay.

Prevailing scientific wisdom at the time was that pinks were the least likely of all the nonnative salmonids to survive and adapt to the fresh, oligotrophic (deep, cold and sterile) waters of Lake Superior. The ability of those first pink salmon to adapt and thrive in the Lake Superior environment was grossly underestimated. In 1959, the first pink salmon caught by anglers in Minnesota tributaries occurred at the Cross and Sucker Rivers.

In their native Pacific environment, pink salmon live out a two-year lifecycle. Spawning in Minnesota waters occurred in odd years up until the 1970’s when the resilient pinks pulled another fast one. First recorded in 1976 in Ontario’s Steel River, it is believed that Lake Superior’s cold environment slowed growth and the rates at which some pinks reached sexual maturity to such a degree, that some fish did not spawn until age-3, thus establishing an even-year run. Later studies of pink salmon otoliths and dorsal spines sampled from the Saint Mary’s River have uncovered age-4 pink salmon, but these are rare. The pink salmon of today continue to spawn in even as well as odd years in varying numbers.

Between the 1960’s and 1970’s, pink salmon populations exploded in record numbers following the common trajectory of a nonnative species introduced into a new environment. Populations peaked in 1979 as pink salmon exceeded the limits of their new home, then naturally decreased reaching equilibrium and the lower numbers we experience today.

Since their initial introduction, pink salmon have adapted quite well to life in Lake Superior. Throughout their native range, pink salmon generally use the first suitable spawning areas encountered during spawning migrations. One competitive advantage pinks have over steelhead and other salmon in Minnesota tributaries is that young pink salmon leave North Shore tributaries almost immediately after hatching. Not having to spend several years competing with other species of fish in the inhospitable conditions and environments of North Shore tributaries is a significant advantage. This also allows adult pinks to successfully exploit a wider range of marginal short-run streams and outflows common to the North Shore for spawning; streams that would otherwise be unsuitable to the longer periods necessary to successfully rear steelhead, coho and chinook salmon. This combination likely results in higher numbers of pink salmon reaching sexual maturity and returning to spawn absent management intervention.

Little is known about the lives of pink salmon in the lake. In their native environment, young pink salmon gather in large schools to feed and evade predators. While they are caught occasionally by boat fisherman and often mistaken for coho, they largely disappear until reappearing as adults when they begin staging for spawning runs off river mouths in August.

Pink Salmon may begin spawning runs any time between late August and mid-September when rainfall causes the streams to rise. Pinks run more reliably and typically in larger numbers in upper shore streams although they can be and are caught as far south as Lester River. The average spawning size is approximately 13” – 16” long weighing in at about a pound, but do get larger and are a blast to catch on lighter gear. Male pink salmon develop a kype as well as a distinct hump on their back during the spawning run, hence the name humpback or humpie/humpy.

Pink salmon deteriorate quickly upon entering the rivers, turning from silver to shades of dark olive-green and in late stages, a whitish fungus also grows on the skin, fins, and tails of the Pinks which is a sure sign the fish are at the end of their life cycle.

Are pinks good to eat? When fresh and silver out of the lake, yes. Pinks as previously mentioned are often misidentified as coho salmon, kept, and eaten when caught while trolling. Pink salmon actually make up the vast majority of the commercial tinned salmon market worldwide.

Once they hit the rivers, they are better suited to smoking provided they are fresh in from the lake and still somewhat silvery as depicted below. They should also be cleaned and iced as quickly as possible.

Pinks can be infuriatingly difficult to catch at times, but with the right techniques and presentations, you may just get to experience what all the hype is about.

Fisheries Management Plan for Minnesota Waters of Lake Superior

This plan is a comprehensive guide on how to best manage Minnesota’s portion of the Lake Superior fishery. The plan is written for use by both the MN DNR Fisheries Management Section and citizens interested in the management of Minnesota’s Lake Superior fishery resource. This plan is based on a fish community approach to fisheries management and highlights why this approach is necessary

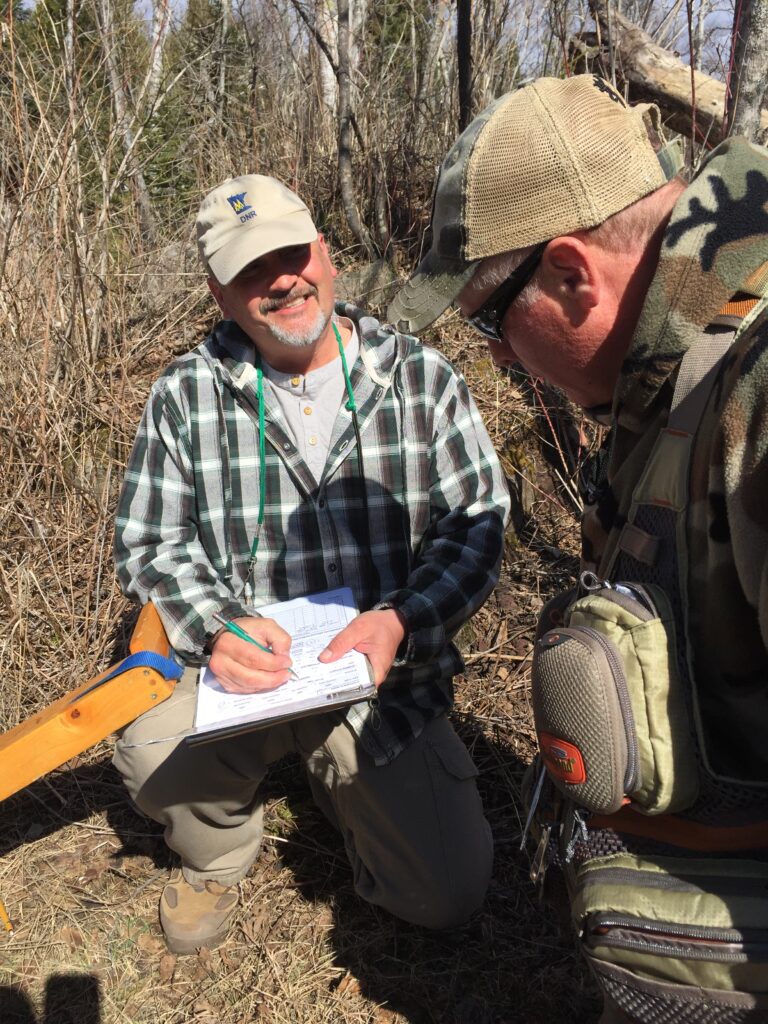

MN DNR Spring Creel Survey

The first spring creel survey was implemented in 1992 to monitor the rehabilitation of Rainbow Trout in Minnesota waters after the species declined in the 1960s. The survey was designed to target anglers who fished for Rainbow Trout as they migrated upstream in tributaries to spawn.

The annual spring creel survey typically begins once tributaries thaw and are fishable. The spring creel survey has provided useful information for many other species in Lake Superior. Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis), one of two native sport fish to Lake Superior, are typically the second most reported species in the spring creel survey.