Lake Superior Chinook Salmon

Chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus. tshawytscha, also known as King salmon, are the largest of all the nonnative salmonid species in Lake Superior.

History: The first attempts to establish chinook salmon in the Great Lakes region were begun in the late-1800’s when 60,000 fry were stocked in the Carp River near Marquette, Michigan. Survival rates for this first generation of chinooks was very low, and the desired natural reproduction resulting from this stocking was not recorded. Efforts to naturalize chinook salmon to the Great Lakes were renewed in 1967 and 1968 when fish were stocked into additional tributaries of Lakes Michigan and Huron.

Chinook salmon have since naturalized, and natural reproduction of Chinook salmon has been documented in Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron although these lakes continue to be stocked annually.

Minnesota: Minnesota first stocked spring-run chinook in 1974, but converted to fall-run chinook salmon in 1979 resulting from disease-free spring-run eggs being unavailable. Minnesota’s goal for a chinook salmon program was to create a put-grow-take fishery. It was assumed that given the short run nature of most Lake Superior tributaries, natural reproduction would not support a self-sustaining population. Natural reproduction is now in fact responsible for the majority of chinook salmon caught by anglers lake-wide however, and most chinook in Minnesota waters today originate from a combination of fish naturally reproduced outside of Minnesota waters, and strays from other State’s stocking programs.

Between 1988 and 2004, summer Lake Superior angler harvest of Minnesota-stocked fish declined from more than 31% to less than 5%. Minnesota’s chinook stocking program was extended following public-input meetings held in 1998, and an outside source of chinook gametes (eggs and sperm) were used for four years from 1999 to 2002. Adult fish returning to the French River trap were used as the brood source beginning in 2003.

The chinook salmon stocking program was also reevaluated at that time. Minimum chinook program continuance criteria were established predicated on annual French River trap return thresholds for mature chinook salmon. Beginning in 2003, if mature chinook returns to French River trap were to fall below 75 BKD-free pairs for three consecutive years, the program would be discontinued.

Bacterial kidney disease (BKD) is a chronic disease caused by the bacterium Renibacterium salmoninarum, and occurs worldwide in salmonids. While BKD has no implications for human health, it is known to cause up to 80% mortality in Pacific salmon, 40% mortality in Atlantic salmon, and presents a significant threat.

According to Minnesota Section of Fisheries, only 13, 20, and 9 pairs of fish were spawned in 2003, 2004, and 2005 respectively. Angler catches of Chinook Salmon in the fall stream fishery declined to 52 fish in 2003 and 292 fish in 2005, despite four years of stocking with at least 350,000 fingerlings from 1999 to 2002.

The low catch and effort by anglers in the fall, combined with low, below BKD threshold returns to the fish traps during spawning, prompted another re-evaluation of the program. As a result, Minnesota stopped stocking chinook salmon in Lake Superior in 2006. Wisconsin followed suit and stopped stocking chinook in Lake Superior in 2007 while Michigan and Ontario have continued to stock chinook in their waters of Lake Superior.

Pinook Salmon – The salmon unicorn

The first documented hybrid between pink salmon and chinook salmon in the Great Lakes was reported in 1992 when a salmon caught in the St. Marys River was submitted to the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) as a world record pink salmon. Unfortunately for the angler it wasn’t a world record pink, but turned out to be something else entirely, a hybrid. Since that time, many St. Mary’s River anglers have reported catching these hybrid ‘pinooks’, and genetic analyses have confirmed the presence of hybridization between pink and Chinook salmon in this system. The St. Mary’s River is the link between Lakes Superior, Huron and Michigan. According to studies conducted on the St. Mary’s from 1999 through 2002, spawning activities of pinks and chinooks overlap heavily in terms of both time and location, and hybridization is in fact common.

50 suspected hybrids were genetically tested and found to contain chinook mitochondrial DNA suggesting that all hybridizations are likely between male pink salmon and female Chinook salmon.

And in Minnesota? Given the low numbers of chinook spawning in Minnesota tributaries it is not likely you’ll catch a Minnesota pinook, but it’s not impossible either. MNST is aware of two fish caught on the North Shore between 2009 and 2021 that are strong contenders. Either way, pinook are real and not just mythical creatures.

Size: The size of chinook salmon often depends on the time of year they are caught. Chinook caught while trolling in the summer typically range from 18″ to 26″ long and weigh about 4 lbs. In the fall, most of the chinook caught are 28″ to 36″ long and weigh 10-12 lbs. Minnesota’s state record for Chinook salmon is 33 lbs. 4 oz. Two fish are tied for the title. One was caught in the Popular River in Cook County, and the other was caught in Lake Superior in St. Louis County.

Diet: While living in their natal streams, young chinook eat a variety of terrestrial insects, aquatic insects, and side swimmers, better known as scuds. After moving to Lake Superior, chinook begin eating variety of fish, especially smelt and ciscoes.

Spawining: In Minnesota, most of the chinook salmon that return to the North Shore to spawn are 3-5 years old. Typically they move near shore in mid-September and wait for October rains before they run up the streams. Actual spawning usually occurs in October and sometimes into early November.

Prior to spawning, males develop a kype. Body coloration darkens to an olive-golden hue, eventually becoming near black. Females excavate redds in suitable gravel, pairing up with a large dominant male and sometimes a couple of lesser males. The female lays her eggs, males fertilize them, and the female covers the eggs with the gravel she removed for the nest. This is repeated until the female has deposited all of her eggs. A single female typically lays 2,000-4,000 eggs, depending on her size. The adults die shortly after spawning.

The eggs hatch in the spring and the alevins spend 2-3 more weeks in the gravel before they swim up and begin to feed. In west coast streams, chinooks remain in the stream for 1 to 2 years before they migrate to the ocean. In North Shore streams, young chinook may migrate to the lake within a few weeks after swimming up which makes them susceptible to predators.

Fishing: Chinooks can appear in streams just about anywhere along the North Shore. Fall-run fish key heavily on rainfall and rising flows so your best bet is to monitor stations, and explore streams when the opportunity arises. Chinooks will readily take egg patterns and various streamers. If you spot a spawning pair, look for competing males that are usually in close proximity to the spawning pair and fish for them instead. If you catch the female, the game is over and you’ll have to move on.

Studies, Plans, & Articles

Click the PDF links below to view/save documents

Fisheries Management Plan for Minnesota Waters of Lake Superior

This plan is a comprehensive guide on how to best manage Minnesota’s portion of the Lake Superior fishery. The plan is written for use by both the MN DNR Fisheries Management Section and citizens interested in the management of Minnesota’s Lake Superior fishery resource. This plan is based on a fish community approach to fisheries management and highlights why this approach is necessary

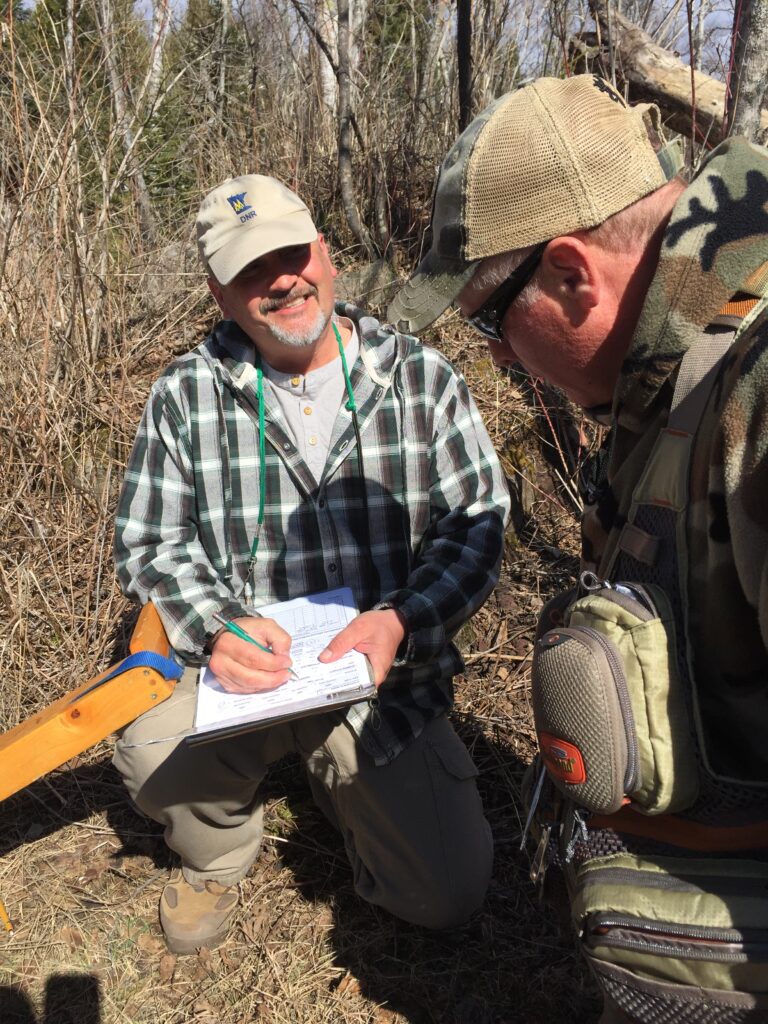

MN DNR Spring Creel Survey

The first spring creel survey was implemented in 1992 to monitor the rehabilitation of Rainbow Trout in Minnesota waters after the species declined in the 1960s. The survey was designed to target anglers who fished for Rainbow Trout as they migrated upstream in tributaries to spawn.

The annual spring creel survey typically begins once tributaries thaw and are fishable. The spring creel survey has provided useful information for many other species in Lake Superior. Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis), one of two native sport fish to Lake Superior, are typically the second most reported species in the spring creel survey.