Lake Superior Brown Trout

Brown trout, Salmo trutta, are a nonnative import to the Great Lakes, and while fall runs on the North Shore are low, fish can be found if you know where to look.

History: Brown trout first arrived from Germany to the U.S. in 1883. First introduced to the Great Lakes region in 1884, brown trout were stocked in a tributary to the Pere Marquette River in Michigan by the U.S. Fish Commission. Created by Congress in 1871, the Commission was the predecessor to the US Fish and Wildlife Service we know today. The three primary, original strains of brown trout were:

Bachforelle – Literally “River Trout” in German, these wary trout were native to the streams of the Black Forest region and parts of Bavaria.

Seeforelle – Literally “Lake Trout” in German, these fish-eating browns were residents of lakes in the Alps. Known as Seeforellen in the U.S., these trout retain migratory characteristics. Preferring deep, cool water lakes, these fish can reach very large sizes under the right conditions in suitable habitat.

Loch Leven – Purported to be the best tasting trout, these Scottish lake-dwelling browns also retain migratory characteristics. The first shipment of carefully-packed eggs left Glasgow, Scotland, in 1884, and arrived in New York via Liverpool, England. Of the first 102,000 eggs that began the long journey to the U.S., 20,000 arrived in Saint Paul, Minnesota, on February 3rd, 1885. Historical accounts regarding what later happened to those first Minnesota eggs are unclear or lost, but by 1900, Loch Leven browns were being stocked in many locations, including the Great Lakes.

Historically, morphological differences between these strains in their native environments certainly existed. And while it’s fun to speculate about the origin of fish we catch today based on body shape, size, spotting patterns such as X’s vs. dots, and spotting colors, these characteristics can no longer be relied upon to determine the underlying original strain of brown trout given the amount of hatchery hybridization that has taken place since the late 1800’s.

Minnesota: Since introduction into Lake Superior in the 1890s, brown trout have established naturalized migratory populations in tributaries, primarily in the longer, relatively barrier-free South Shore tributaries of Wisconsin. Attempts to establish migratory populations in a number of Minnesota streams has yielded very limited success. Brown Trout are rarely caught in tributary streams below barriers, and are only occasionally caught during the summer boat fishery based on summer creel surveys.

According to the 2017 Fisheries Management Plan For The Minnesota Waters Of Lake Superior, “Experimental stocking of 63,000 yearling and 170,000 fingerling Brown Trout in the St. Louis River from 1985 to 1987 failed to significantly increase the catch in the summer boat fishery from 1988 to 1992. Fish caught in Minnesota are the result of limited natural reproduction below the barriers, fish migrating down to the lake from above the first barrier, and fish originating from other states, and in particular from Wisconsin, which stocked about 100,000 age-1 Brown Trout per year from 2006 to 2014. Habitat for Brown Trout along Minnesota’s shoreline and tributaries below the first barrier is marginal, as it is for other fall-spawning migratory species.”

Brown Trout have not been stocked below barriers in Lake Superior tributaries in Minnesota since 1987; however, brown trout continue to be stocked above barriers in some lower North Shore tributary streams.

Size: Lake run browns in Minnesota waters tend to be long, sleek fish around 18″ and weighing about 2lbs. on average. These fish can however exceed 25″ and weigh upwards of 12lbs. The Minnesota state record for a brown trout is 16lbs. 12oz. Because brown trout are naturally wary and somewhat resistant to fishing pressure, they can easily get to be 5-7 years old.

Diet: Brown trout are active feeders and the goats of the trout family. Browns seem to eat anything and everything that crawls, swims, walks, hops or is unlucky enough to fall into the water while flying by. Seemingly, if a brown is big enough to swallow it, they’ll eat it. While the list doesn’t include tin cans, it does include: zooplankton, aquatic and terrestrial insects and their larvae, crustaceans, mollusks, arthropods such as crayfish, worms, amphibians, small rodents, and fish including other brown trout. In a few documented cases, large browns have been known to eat young mink and small turtles.

Spawning: Maturing in 3-4 years, most browns will spawn multiple years and often near or in he same location used in prior years, typically between October and December. Absent barriers common to most North Shore streams, brown trout will swim up into headwaters areas to spawn, selecting locations similar to those preferred by brook trout. These locations usually contain gravel bottoms in areas with spring seeps and consistent moving water. After pairing up, the females excavates a redd which the male defends until the female is ready to deposit eggs. This process will be repeated until all eggs are deposited, and female brown trout will lay between 400 to 2,000 eggs depending on her size. Brown trout do not die after spawning.

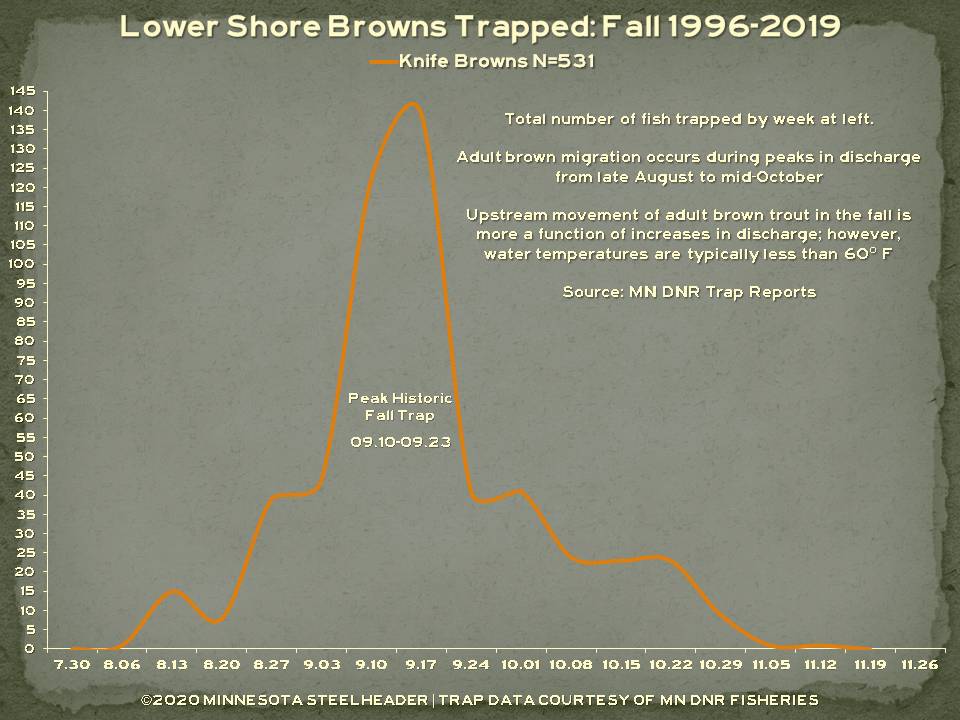

Despite not spawning until later in the year, brown trout may begin returning to North Shore streams as early as August, with a strong historical peak between September 10th and September 23rd as depicted below. Brown returns to Minnesota tributaries are low as previously mentioned. From 1996 to 2019, returns to the Knife River averaged just 23 fish per year.

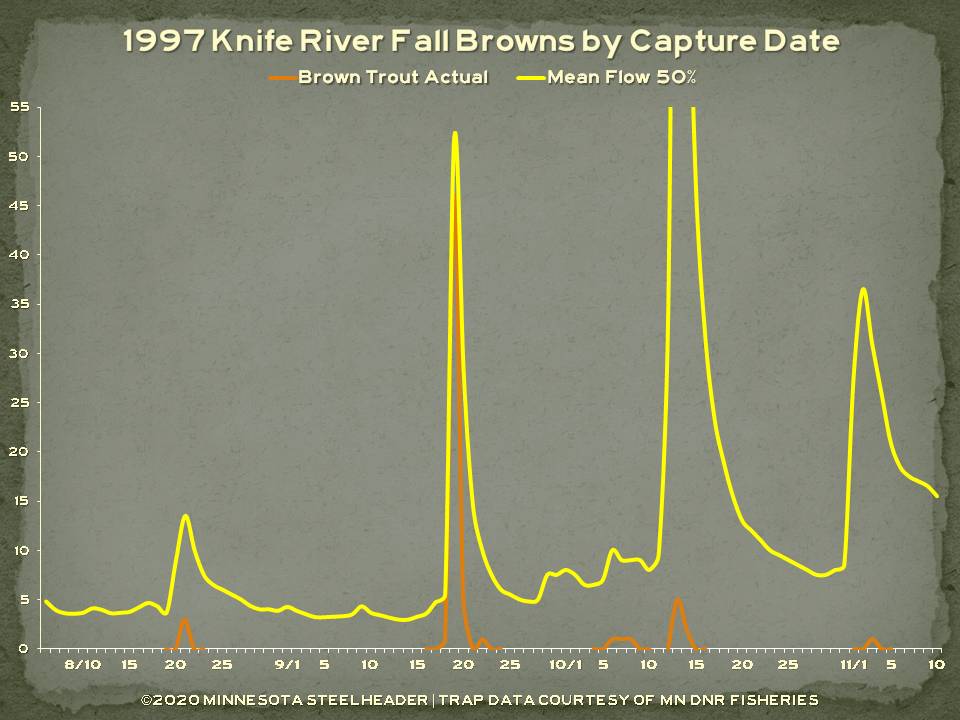

Fishing: Your best bet for locating browns are to fish Lower Shore streams in September following precipitation events that increase flows. The chart below illustrates brown trout captured at the Knife River trap by capture date for 1997. Note the strong migration correlation to flows depicted in yellow. Virtually all fall trap charts regardless of species and year show the same type of correlation between flows and returns. In fall, it is absolutely all about the flow.

Browns on the North Shore are a tough nut to crack. They can be caught but you will have to put the time and effort in, and it helps to know which streams have documented runs of brown trout. Once you identify those, it just a matter being in the right place at the right of time. Paying attention to the two charts above will go a long way towards putting you on the water at the right time, figuring out that “secret stream” is up to you.

Fisheries Management Plan for Minnesota Waters of Lake Superior

This plan is a comprehensive guide on how to best manage Minnesota’s portion of the Lake Superior fishery. The plan is written for use by both the MN DNR Fisheries Management Section and citizens interested in the management of Minnesota’s Lake Superior fishery resource. This plan is based on a fish community approach to fisheries management and highlights why this approach is necessary

MN DNR Spring Creel Survey

The first spring creel survey was implemented in 1992 to monitor the rehabilitation of Rainbow Trout in Minnesota waters after the species declined in the 1960s. The survey was designed to target anglers who fished for Rainbow Trout as they migrated upstream in tributaries to spawn.

The annual spring creel survey typically begins once tributaries thaw and are fishable. The spring creel survey has provided useful information for many other species in Lake Superior. Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis), one of two native sport fish to Lake Superior, are typically the second most reported species in the spring creel survey.